Last week I said there are Three Simple Rules for Better Broadcast Writing. And yes, they are simple. No rule has more than ten words. Each rule is straightforward. Each is easy to understand.

I also said the simplicity was deceptive.

The deception comes not in learning the rules, but rather in sticking to them. Unlike novelists, who answer only to the demands of the marketplace, journalists have strict deadlines. Miss a deadline and you quickly become a former journalist. Given the pressure, it’s a wonder many stories even come out in prose! So how can you be expected to crank out literature under that kind of time constraint?

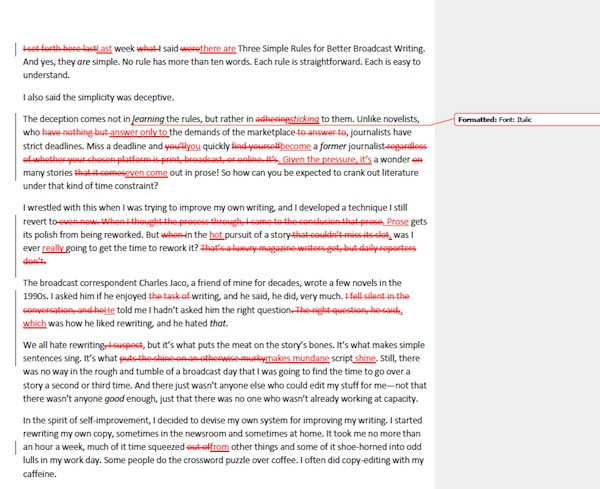

A word-processing “compare document” showing the changes made between the first and second drafts of this post.

I wrestled with this when I was trying to improve my own writing, and I developed a technique I still revert to. Prose gets its polish from being reworked. But in the hot pursuit of a story, was I ever really going to get the time to rework it?

The broadcast correspondent Charles Jaco, a friend of mine for decades, wrote a few novels in the 1990s. I asked him if he enjoyed writing, and he said, he did, very much. He told me I hadn’t asked him the right question, which was how he liked rewriting, and he hated that.

We all hate rewriting, but it’s what puts the meat on the story’s bones. It’s what makes simple sentences sing. It’s what makes mundane script shine. Still, there was no way in the rough and tumble of a broadcast day that I was going to find the time to go over a story a second or third time. And there just wasn’t anyone else who could edit my stuff for me—not that there wasn’t anyone good enough, just that there was no one who wasn’t already working at capacity.

In the spirit of self-improvement, I decided to devise my own system for improving my writing. I started rewriting my own copy, sometimes in the newsroom and sometimes at home. It took me no more than an hour a week, much of it time squeezed from other things and some of it shoe-horned into odd lulls in my work day. Some people do the crossword puzzle over coffee. I often did copy-editing with my caffeine.

My process was pretty regimented.

- First, I’d work on stories that were several days old. The reason is that I wanted to get enough distance from them so that I wasn’t wrestling with me, just with some mangled words.

- Second, it wasn’t enough to re-read a script and mentally work through a rewrite. I forced myself to use a pencil or, even better, a red pen to strike through words, rearrange phrases, and reorder sentences.

- Third, I was ruthless. It was old news, so it really didn’t matter what it looked like when I got finished with it.

From my first pass through my past prose, my writing improved. Phrases that were close but not quite there, got there easily. I had a field day substituting the right word for what Mark Twain called “its second-cousin.” Structure that seemed like a good bet at first could almost always be improved.

I saw myself polishing my writing. But I really wasn’t improving it. I was rewriting old news. My marked-up scripts weren’t even good for wrapping fish!

But I noticed something was starting to change in the way I wrote my deadline stuff. Chronic errors I had been making started to get less chronic. I was cutting words before I put phrases on paper, picking more precise nouns and verbs and using fewer modifiers, and getting cleaner, shorter sentences.

It took me awhile to figure out what was happening. The effort I put into crossing things out, moving them to different places, and reworking my words had made me more aware of what was going into my stories before it went in. The time I spent wrestling with past scripts trained me for what to do in future scripts.

Was the hour a week I invested in my writing the most onerous thing I’ve had to do in 35 years in news? Not by a long shot! (The weekend overnight assignment desk will probably bear that torch for the rest of my life.)

After seeing my writing improve over six months, I figured if I wasn’t already at the Altar of Prose, I was pretty close. I slacked off the rewriting exercises. Soon, my writing slacked off. So I went back to sporadic rewrite sessions, and I’ve maintained them ever since. Some years ago, when I was asked to come up with rules for good writing, Solitary Script Rewriting became number four on my list.

It’s such an important exercise that I even put this through the rewrite wringer. Have a look here at how it improved.